The term “stromatolite” was introduced in 1908 by Kalkowsky to describe structures found in the Lower Triassic of Germany. The word stromatolite comes from the Greek stroma, meaning “layer” or “covering.” For many years, stromatolites were thought to have a non-biological origin. This view changed in 1954, when microscopic fossil algae were discovered in the Gunflint Iron Formation (Precambrian, Ontario). This discovery confirmed the hypothesis proposed earlier by C. D. Walcott (1850–1927), who had already recognized similar algal structures in North America at the beginning of the twentieth century.

Stromatolites are biosedimentary structures that have been classified mainly on the basis of their external shape. These classifications are descriptive and do not reflect their origin, since the same stromatolite can be produced by different algal communities. A useful distinction is made between true stromatolites and oncoids. True stromatolites are laminated or massive structures formed by algal mats that are attached to the substrate from the beginning and grow in situ. Oncoids, instead, are not attached to the substrate during their formation.

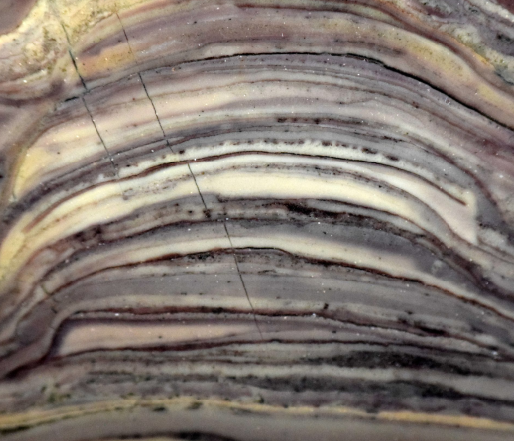

Stromatolites are sedimentary bodies anchored to a substrate, whose original shape they follow. They consist of a series of thin sedimentary layers (laminae) with variable thickness and composition. These layers are produced by algal activity and are stacked one above the other. The laminated structure is clearly visible in side views and in vertical sections. In cross-sections, stromatolites appear as irregular concentric circles or ellipses.

The shape and internal structure of stromatolites are strongly influenced by the physical and chemical conditions of the environment. Although they are built by algal communities, stromatolites should not be classified using biological taxonomy. They are not fossil organisms, but sedimentary bodies formed by the activity of benthic algal communities. For this reason, names such as Cryptozoan and Collenia should not be used as taxonomic terms, although they may still be used in a purely morphological sense.

The terms Cryptozoan and Collenia derive from early attempts to classify organo-sedimentary carbonate structures now recognized as stromatolites. Cryptozoan was used as a broad descriptive term for biologically influenced carbonate structures of uncertain origin and included a wide range of morphologies. Due to its lack of morphological and genetic precision, the term is now considered obsolete.

Collenia, introduced by Walcott, referred to a specific type of domal, laminated stromatolite and was treated as a biological genus. This interpretation is no longer accepted, as stromatolites are sedimentary structures produced by microbial communities rather than fossil organisms. Consequently, both terms lack taxonomic validity and may be retained only in a historical or purely morphological context.

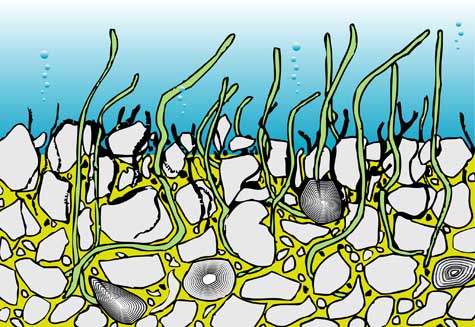

The laminae are made of aragonite or, more commonly, calcite, together with fine detrital sediments. Their thickness usually does not exceed one millimeter. They form through the direct and indirect activity of non-calcareous benthic algae, mainly cyanobacteria (blue-green algae), as well as green algae and probably red algae.

Thrombolites are closely related biosedimentary structures but differ from stromatolites in their internal organization. While stromatolites show a well-developed laminated fabric, thrombolites are characterized by a clotted or patchy internal texture, lacking regular lamination. This texture results from the growth of microbial communities in discrete aggregates rather than in continuous mats. Thrombolites are also produced mainly by microbial activity, especially cyanobacteria, and are influenced by environmental factors such as water energy, sediment supply, and carbonate saturation. Like stromatolites, thrombolites are common in the Precambrian record, but they also occur in younger geological periods and in some modern environments.

From a bathymetric perspective, these organo-sedimentary structures show a clear relationship with light availability. Stromatolite-forming algal communities are therefore most commonly associated with warm, shallow marine environments, although stromatolitic structures have been reported at depths of up to 150 meters (Playford & Cockbain, 1969; Hoffman, 1974). While such depths may appear surprising, they can be explained by the high adaptability of certain algal and microbial communities to a wide range of environmental conditions.

Although, under exceptional conditions of preservation and sedimentation, imprints and traces of algal filaments have been observed on the upper and lower surfaces of individual laminae (Gregoire & Monty, 1962), it is generally impossible to identify the genus or species of the algae responsible for stromatolite construction.

With regard to overall morphology and lamina geometry, only interpretative models can be proposed. The curvature and concentric arrangement of laminae are thought to result from a combination of sedimentary factors (such as sedimentation rate) and environmental energy (wave action and currents). The typical domal shape of many stromatolites may also be linked to the upward bending of the initial lamina, possibly caused by the production of hydrogen sulfide during the decay of algal mats at the sediment–water interface.

Genesis and evolution of stromatolites

Algal communities that colonize and stabilize the seafloor create a microenvironment in which calcium carbonate precipitation, mainly as aragonite, occurs due to algal metabolic activity. Needle-shaped aragonite crystals are deposited and trapped within the microbial mat, together with fine detrital sediments. Progressive sediment accumulation eventually smothers the algal mat, which then re-establishes itself above the previous layer, producing a cyclic, laminated structure.

Because most stromatolites form in shallow marine or intertidal environments, and because lamina thickness depends partly on the input of fine detrital sediments, stromatolites are considered excellent paleoenvironmental indicators. They provide valuable information not only on marine conditions but also on the climate and morphology of adjacent continental areas.

The carbonate component of stromatolites is controlled by algal biochemical activity and is therefore linked to light availability, seasonal cycles, and day–night rhythms. In contrast, the detrital component depends on climatic conditions and erosion processes affecting nearby landmasses. In the absence of terrigenous input, lamina formation is entirely due to biogenic carbonate precipitation, often referred to as algal dust.

Stromatolites represent the earliest reliable evidence of lithogenic biological activity on Earth. From the Precambrian to the Holocene, they form a nearly continuous record of microbial life that constituted the base of marine food webs and, more broadly, of life itself. Their sharp decline since the late Paleozoic is likely related to the rise of benthic grazing organisms and to increasing competition with coralline red algae during the Mesozoic.

The ability of stromatolite-forming microbial communities to adapt to freshwater, marine, and hypersaline environments places them among the most stress-tolerant life forms. Without such adaptability, biological crises throughout Earth’s history might have been far more severe.

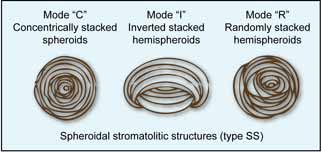

Three main morphological end-members are commonly recognized, with many transitional forms between them:

- LLH (Laterally Linked Hemispheroids) – domal forms laterally connected by continuous laminae; domes may be closely packed (LLH-C) or separated by flat surfaces (LLH-S).

- SH (Stacked Hemispheroids) – vertically stacked domes forming columns, separated by sediment; columns may have constant (SH-C) or variable (SH-V) diameters.

- SS (Spheroidal Structures) – structures surrounding a mobile nucleus of organic or inorganic origin; laminae may be concentric (SS-C), irregular (SS-R), or inverted (SS-I).

Different end-member types may occur within the same stromatolitic association and at different observation scales. For example, SH-type stromatolites may be internally composed of LLH-C laminae.

The main aggregation types are illustrated in the referenced plates (redrawn after Aitken, 1967; and Reijers & Hsü, 1986).